Directors Discourse: Interview with an Indian Master

Adoor Gopalakrishnan is one of India's greatest filmmakers. He has scripted and directed eleven feature films and several shorts and documentaries. Adoor is the pioneer of the New Cinema movement in Kerala.

Firstly, there is the hurdle of language. I make films in Malayalam and this limits the audience for my movies to Kerala. My films can very well be subtitled in English. We lack an intelligent and enlightened distribution system that does not hesitate to explore new avenues for a different kind of cinema.

Do you think there is an audience for world cinema in India?

There certainly is. You can gauge the interest from the success of the several film festivals spread all over India now. Especially with the advent of the multiplex, it is possible to program decent films and generate reasonable revenue. But distributors should have faith in these films and be ready to venture into unexplored areas.

How true are you to your script? Is there room for improvisation during the shoot?

I always work with a detailed script. And then I prepare a shooting script before I go for a shoot. All the same, no script is sacrosanct when you actually film on locale.

Scripting is perhaps the most important stage of filmmaking. But it should not be treated as final and inviolable. A script is written inside a room, but on location where you have nature and real people interacting, there is every little chance for changes. Even the position of the sun in the day becomes a very critical factor.

What is editing to you? Do your films evolve in the editing room?

Editing begins even as you are writing your script. It accords the film its rhythm and flow. It is again not necessary that editing follows the script strictly. In fact I do not refer to the script while editing. Though a lot of thought and planning may have gone into scripting, the editor/director should not hesitate to improve upon the material available to him. There are many instances of my having altered the sequence of the scenes even. The impact is what matters.

If we talk about Indian cinema gone global, two prolific names come to mind immediately; Satyajit Ray and yourself. Why is it so?

It may be because whe have not compromised with market pressures. These films deal with real people, their problems and their aspirations. Nothing is faked for dramatic or spectacular effect. As these films portray life lived in our land they become authentic documents of Indian life.

Would you make a film in Hindi like Ray did?

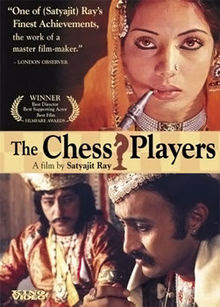

(Laughs) I don't see the need. Also, my understanding of the Hindi language is very rudimentary. And don't forget, language is the flower of a culture. It is not just a mere vehicle to transact ideas. It should not be forgotten that Ray made only on attempt at making a film in Hindi (Shatranj Ke Khilari-1977).

In Nizhalkuthu (2002) you have followed a rhythm different from your other films. It is fast paced, stylistically shot and features a mainstream music composer (Ilaiyaraaja). Was that a successful experiment?

Each time I make a film, my attempt is to try things I have not done before. So, every time I pose before myself a new challenge and then try to meet it. The process is very exciting. Some films are slow while others are faster. The pace of a film is invariably dependent on its theme and treatment. As for the score, I wanted to use folk music as a lait motif. Ilaiyaraaja happens to be a master at that and it worked very well. I was very happy with the result.

In Kodiyettam (1977), the lead character, Shankarankutty slowly sheds his childlike conduct after his marriage. In Swayamvaram (1972) marriage is seen as a rude wakeup call from a love story. Do you see marriage as a failed institution?

No. In fact, I see it the other way. Marriage is the meeting of two minds. Shankarankutty who is not prepared for a married life and the responsibilities that come with it, slowly grows into it. His real marriage takes place at the very end when he buys clothes and presents it to his wife. A man presenting clothes to the woman is a core ritual of Hindu marriage in Kerala. Swayaramvaram is the story of a young man and a woman choosing to live together without the formal bonding of a marriage. It is devoid of the supportive network of their parents. It is the society that they come into that proves to be unwilling to accommodate them.

You stand against popular cinema. What factors you think would allow parallel cinema to survive in India?

I am not against cinema becoming popular. We all want our films to be popular. In their effort to make their films acceptable to the masses, people make all kinds of compromises and the end product turns out to be simply run of the mill. Let me hasten to add that I do not make parallel cinema. Parallel cinema is a misnomer. I simply make films. It is others who call them by convenient names and I think it is unfair to do so. My films are processed in the same laboratories as the commercial ones and often I use commercially successful stars in them. I exhibit them in the same cinemas as the others. There is nothing in the making, promotion and exhibition of these films, which qualifies them to be termed parallel. Quality films deserve to be treated differently. We can borrow examples from the west. Both in Europe and the US, if a film wins a good prize in an international festival, it becomes a selling point. Our own experience is just the opposite. A film winning a National award is looked down upon with suspicion. Our distributors discreetly avoid it because they assume that popularity or commercial success is inversely proportional to the quality of a film.

Adoor Gopalakrishnan was interviewed by Apurva Asrani, himself an award-winning editor and a filmmaker based in Mumbai, India. Asrani has a multimedia body of work in film, television and theater.

According to an account of the British Film Institute only two filmmakers from India have won the BFI’s Sutherland Trophy for most original and imaginative film — Satyajit Ray and Adoor Gopalakrishnan. Adoor has won the International Film Critics Prize six times, and in 2002 the Smithsonian Institution honoured him with a complete retrospective of his work.

Adoor pioneered the film society movement in Kerala and formed India’s first film co-operative for production, distribution and exhibition. In the clip below he answers questions from Twitter, Facebook and email, as part of the BFI's Ask an Expert series.

Click for a Short List of Movies of A. Gopalakrishnan

Interview

Why are your films not widely available in India?

Interview

Why are your films not widely available in India?

Firstly, there is the hurdle of language. I make films in Malayalam and this limits the audience for my movies to Kerala. My films can very well be subtitled in English. We lack an intelligent and enlightened distribution system that does not hesitate to explore new avenues for a different kind of cinema.

Do you think there is an audience for world cinema in India?

There certainly is. You can gauge the interest from the success of the several film festivals spread all over India now. Especially with the advent of the multiplex, it is possible to program decent films and generate reasonable revenue. But distributors should have faith in these films and be ready to venture into unexplored areas.

How true are you to your script? Is there room for improvisation during the shoot?

I always work with a detailed script. And then I prepare a shooting script before I go for a shoot. All the same, no script is sacrosanct when you actually film on locale.

Scripting is perhaps the most important stage of filmmaking. But it should not be treated as final and inviolable. A script is written inside a room, but on location where you have nature and real people interacting, there is every little chance for changes. Even the position of the sun in the day becomes a very critical factor.

What is editing to you? Do your films evolve in the editing room?

Editing begins even as you are writing your script. It accords the film its rhythm and flow. It is again not necessary that editing follows the script strictly. In fact I do not refer to the script while editing. Though a lot of thought and planning may have gone into scripting, the editor/director should not hesitate to improve upon the material available to him. There are many instances of my having altered the sequence of the scenes even. The impact is what matters.

If we talk about Indian cinema gone global, two prolific names come to mind immediately; Satyajit Ray and yourself. Why is it so?

It may be because whe have not compromised with market pressures. These films deal with real people, their problems and their aspirations. Nothing is faked for dramatic or spectacular effect. As these films portray life lived in our land they become authentic documents of Indian life.

Would you make a film in Hindi like Ray did?

(Laughs) I don't see the need. Also, my understanding of the Hindi language is very rudimentary. And don't forget, language is the flower of a culture. It is not just a mere vehicle to transact ideas. It should not be forgotten that Ray made only on attempt at making a film in Hindi (Shatranj Ke Khilari-1977).

In Nizhalkuthu (2002) you have followed a rhythm different from your other films. It is fast paced, stylistically shot and features a mainstream music composer (Ilaiyaraaja). Was that a successful experiment?

Each time I make a film, my attempt is to try things I have not done before. So, every time I pose before myself a new challenge and then try to meet it. The process is very exciting. Some films are slow while others are faster. The pace of a film is invariably dependent on its theme and treatment. As for the score, I wanted to use folk music as a lait motif. Ilaiyaraaja happens to be a master at that and it worked very well. I was very happy with the result.

In Kodiyettam (1977), the lead character, Shankarankutty slowly sheds his childlike conduct after his marriage. In Swayamvaram (1972) marriage is seen as a rude wakeup call from a love story. Do you see marriage as a failed institution?

No. In fact, I see it the other way. Marriage is the meeting of two minds. Shankarankutty who is not prepared for a married life and the responsibilities that come with it, slowly grows into it. His real marriage takes place at the very end when he buys clothes and presents it to his wife. A man presenting clothes to the woman is a core ritual of Hindu marriage in Kerala. Swayaramvaram is the story of a young man and a woman choosing to live together without the formal bonding of a marriage. It is devoid of the supportive network of their parents. It is the society that they come into that proves to be unwilling to accommodate them.

|

| Nizhalkuthu |

I am not against cinema becoming popular. We all want our films to be popular. In their effort to make their films acceptable to the masses, people make all kinds of compromises and the end product turns out to be simply run of the mill. Let me hasten to add that I do not make parallel cinema. Parallel cinema is a misnomer. I simply make films. It is others who call them by convenient names and I think it is unfair to do so. My films are processed in the same laboratories as the commercial ones and often I use commercially successful stars in them. I exhibit them in the same cinemas as the others. There is nothing in the making, promotion and exhibition of these films, which qualifies them to be termed parallel. Quality films deserve to be treated differently. We can borrow examples from the west. Both in Europe and the US, if a film wins a good prize in an international festival, it becomes a selling point. Our own experience is just the opposite. A film winning a National award is looked down upon with suspicion. Our distributors discreetly avoid it because they assume that popularity or commercial success is inversely proportional to the quality of a film.

|

| Apurva Asrani |

Adoor Gopalakrishnan was interviewed by Apurva Asrani, himself an award-winning editor and a filmmaker based in Mumbai, India. Asrani has a multimedia body of work in film, television and theater.

nice to read this interview. there is a typo tho 'A script is written inside a room, but on location where you have nature and real people interacting, there is (E)very little chance for changes(s).'

ReplyDeleteThis is the second posting for my reply to you! The first one just vanished! So thanks for pointing out the typo. Just one letter makes such a huge difference in meaning! Thank you!

Deletenice surprise to see this interview posted here. Have you seen Shahid? A new film that I worked on. Would love to read a blog on that from you. Regards. AA

ReplyDeleteI am delighted to have Asrani himself, the artist and interviewer, comment with an obvious spirit of sharing and approval. Thanks Asrani for taking the time to add credulity and transparency to my endeavor to familiarize my readers to different cultures through the media of cinema and literature. Indian cinema, by the way, is a major contributor to my cultural upbringing in Africa before I move to Canada. As for Shahid, I will most certainly seek to see and write on it with added motivation. You will see a note in my Facebook page on this exchange.

ReplyDeletehttps://www.facebook.com/groups/yamustafayamuhtawa/